Editor's note: Sally Kohn is a progressive activist, columnist and television commentator. Follow her on Twitter @sallykohn.

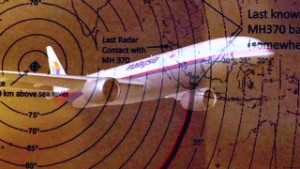

(CNN) -- It makes sense that we're all obsessed with the missing Malaysia Airlines flight 370. What I find more mysterious is why we aren't obsessed with other arguably more important stories.

The missing Malaysia Airlines plane falls right at the nexus of several gripping story lines in the public narrative. Stories about death inherently hold our attention. The more dark among us -- and HBO producers -- might attribute this to a lust for the gruesome. Freud would simply call it our "death drive" — that mix of fear and fascination that our lives must ultimately end. Regardless, as Jack Schaeffer noted in Reuters, media coverage has always hewed toward dark sensationalism to feed the cravings of a hungry audience.

Sally Kohn

Sally Kohn There's something about death in sudden, large numbers that grabs our attention. Every year, about 32,000 people are killed by guns in the United States. And yet the routine daily suicides and shootings don't seem to command our attention or even our compassion in quite the same way as mass shootings like Aurora or Sandy Hook. Of course, we also respond to whom the victims are: When they are innocent little children, the dismay is more intense.

It's not just about numbers — the idea that suddenly a large group of people are harmed. While the unknown fate of the 239 souls aboard the Malaysia flight is unquestionably looming with tragedy, on the same day the plane went missing around 20,000 people died from cancer worldwide. Around 4,000 people worldwide died from AIDS on the same day. In the 11 days since the plane has been missing, more than 1,000 people have likely died from drug overdoses in the United States alone. Why don't we care about these tales of death? Or perhaps more important, how could we care more?

The other gripping story line of the missing Malaysia flight is, of course, the mystery. It's a real whodunnit unfolding live before our very eyes. Adding to the fascination is certainly the fact that, as Farhad Majoo eloquently pointed out in the New York Times, a genuine mystery would seem impossible in our hyper-connected, over-surveilled day and age.

Majoo writes: "The disappearance stands in stark contrast to the hallmark sensation of our time, the certainty that we're all being constantly tracked and that, for better or worse, we're strapped to the grid, never out of touch. It turns out that's not true."

Families frustrated with lack of info

Families frustrated with lack of info  Malaysia probe focuses on westerly turn

Malaysia probe focuses on westerly turn  Pilot was 'against any form of extremism'

Pilot was 'against any form of extremism' But if that is really the hallmark norm of our era, then why aren't we equally fixated on the fact that in this day and age, 1 million children are exploited by the global commercial sex trade every single year — many disappearing right out from under the eyes of loved ones or government agencies. Shocking, right? But worthy of our 24/7 attention? Apparently not.

"The problem with our always-on culture is that actually, we're not always focused on stuff that matters, just stuff that triggers," says Micah Sifry, co-founder of the Personal Democracy Forum. "The news business has long understood this, but now the rise of social media seems to be making the problem even worse, since it is fragmenting our attention down to the individual level."

Still it raises the question -- what about the things that arguably matter and on some level trigger, just not enough? Is there a way to make the daily scourge of AIDS and child sex trafficking and gun violence as gripping as a missing jumbo jet?

No, says Bea Arthur, a licensed therapist and founder of PrettyPaddedRoom.com. Arthur argues its not just the conflation of compelling plot lines that makes the Malaysia plane story so gripping — it's the fact that it's a lot of people, that it happened suddenly, and that we still don't know what happened. What grabs us is the idea that a plane can suddenly, unpredictably drop out of the sky. It ruptures our need for control.

"People want details because they want to know this won't happen to them," Arthur says. Arthur suggests our fascination with tragedies like the Malaysia plane is less about the basic facts of death or scale or even mystery but simply the egotistical desire to categorically exempt ourselves from whatever new possibility of bad things happening arise out of the story. "It's about ego and self-preservation and wanting some sense of control," Arthur says.

In other words, even though we are more likely to die from cancer (1 in 4 odds for men, 1 in 5 odds for women) than a plane crash (1 in 11,000,000 million odds), cancer feels like a known, even avoidable threat (even if it's not) whereas the missing plane pushes our personal panic button.

The media can keep trying to tell the stories of poor people dying from lack of food and shelter, of children in rural communities and inner cities dying from gun violence, of black and Latina woman disproportionately being infected with and dying from HIV/AIDS. These stories are vital, especially when told in careful ways that don't just elicit individual sympathy but illuminate larger structural implications and the need for solutions. But no matter how numerous, no matter how gruesome and no matter how pressing, these and other critical stories may never pierce our consciousness, let alone capture world attention.

Then again, Arthur points out, the Malaysia plane story is only interesting until it ends.

"Once there's closure ... we'll go on and forget about it, too," she says. "Strange comfort that, in the end, all stories — important or intriguing or in between — fall victim to our short attention span.

{ 0 comments... read them below or add one }

Post a Comment