On CNN TV: Superstorms are a new breed of weather that put lives and cities that were once protected in the eye of their fury. Are we ready for the next one? Watch CNN's "The Coming Storms" on Sunday, January 6, at 8 p.m. and 11 p.m. ET.

(CNN) -- They hover above our heads, out of sight, zooming in and taking pictures.

They aren't interested in the latest celebrity wedding or covert military operation. And the images they take aren't going to make the front page of any magazine or website.

But maybe they should.

That's because the data collected by these powerful satellites have helped save countless lives by allowing meteorologists to warn people about dangerous storms -- sometimes a week before they strike -- with pinpoint accuracy.

Seven days before Superstorm Sandy hit the United States on October 29, computer models based on the data from these satellites predicted the storm would make landfall in New Jersey.

Opinion: What's next after Superstorm Sandy?

It landed just five miles from where the earliest forecasts said it would.

"It is unprecedented," said Chad Myers, CNN's severe weather expert and meteorologist. "(No) other storm in recent memory has been forecast that good for that long.

Satellite went down before Sandy struck

Satellite went down before Sandy struck  Scientist: Sandy a taste of things to come

Scientist: Sandy a taste of things to come  Obama: Focus on jobs, not climate change .cnnArticleGalleryNav{border:1px solid #000;cursor:pointer;float:left;height:25px;text-align:center;width:25px} .cnnArticleGalleryNavOn{background-color:#C03;border:1px solid #000;float:left;height:25px;text-align:center;width:20px} .cnnArticleGalleryNavDisabled{background-color:#222;border:1px solid #000;color:#666;float:left;height:25px;text-align:center;width:25px} .cnnArticleExpandableTarget{background-color:#000;display:none;position:absolute} .cnnArticlePhotoContainer{height:122px;width:214px} .cnnArticleBoxImage{cursor:pointer;height:122px;padding-top:0;width:214px} .cnnArticleGalleryCaptionControl{background-color:#000;color:#FFF} .cnnArticleGalleryCaptionControlText{cursor:pointer;float:right;font-size:10px;padding:3px 10px 3px 3px} .cnnArticleGalleryPhotoContainer cite{background:none repeat scroll 0 0 #000;bottom:48px;color:#FFF;height:auto;left:420px;opacity:.7;position:absolute;width:200px;padding:10px} .cnnArticleGalleryClose{background-color:#fff;display:block;text-align:right} .cnnArticleGalleryCloseButton{cursor:pointer} .cnnArticleGalleryNavPrevNext span{background-color:#444;color:#CCC;cursor:pointer;float:left;height:23px;text-align:center;width:26px;padding:4px 0 0} .cnnArticleGalleryNavPrevNextDisabled span{background-color:#444;color:#666;float:left;height:23px;text-align:center;width:25px;padding:4px 0 0} .cnnVerticalGalleryPhoto{padding-right:68px;width:270px;margin:0 auto} .cnnGalleryContainer{float:left;clear:left;margin:0 0 20px;padding:0 0 0 10px}

Obama: Focus on jobs, not climate change .cnnArticleGalleryNav{border:1px solid #000;cursor:pointer;float:left;height:25px;text-align:center;width:25px} .cnnArticleGalleryNavOn{background-color:#C03;border:1px solid #000;float:left;height:25px;text-align:center;width:20px} .cnnArticleGalleryNavDisabled{background-color:#222;border:1px solid #000;color:#666;float:left;height:25px;text-align:center;width:25px} .cnnArticleExpandableTarget{background-color:#000;display:none;position:absolute} .cnnArticlePhotoContainer{height:122px;width:214px} .cnnArticleBoxImage{cursor:pointer;height:122px;padding-top:0;width:214px} .cnnArticleGalleryCaptionControl{background-color:#000;color:#FFF} .cnnArticleGalleryCaptionControlText{cursor:pointer;float:right;font-size:10px;padding:3px 10px 3px 3px} .cnnArticleGalleryPhotoContainer cite{background:none repeat scroll 0 0 #000;bottom:48px;color:#FFF;height:auto;left:420px;opacity:.7;position:absolute;width:200px;padding:10px} .cnnArticleGalleryClose{background-color:#fff;display:block;text-align:right} .cnnArticleGalleryCloseButton{cursor:pointer} .cnnArticleGalleryNavPrevNext span{background-color:#444;color:#CCC;cursor:pointer;float:left;height:23px;text-align:center;width:26px;padding:4px 0 0} .cnnArticleGalleryNavPrevNextDisabled span{background-color:#444;color:#666;float:left;height:23px;text-align:center;width:25px;padding:4px 0 0} .cnnVerticalGalleryPhoto{padding-right:68px;width:270px;margin:0 auto} .cnnGalleryContainer{float:left;clear:left;margin:0 0 20px;padding:0 0 0 10px}  Low temperatures in Switzerland helped freeze Lake Geneva in early February. Rita Rautenbach got this amazing shot at the time. "'During the night and the day before, we had extreme temperatures where it got so cold that the spray made waves on the lake. As it sprays up it turns into ice immediately. It became layer on layer on layer. It became thick blocks of ice on the bench, on the cars." Hospital rooms were completely destroyed after a tornado hit Harrisburg, Illinois in February. Jane Harper, a nurse there, took this photo after moving patients out of harm's way. She went to check one of the patient rooms, and found that the room was no longer there. A lightning storm lit up the Bay Bridge in San Francisco, California in April. Phil McGrew shot 20-second exposures for 90 minutes in order to get shots like this. Severe flooding in Duluth, Minnesota, in June destroyed roads and left neighborhoods underwater. "We have not experienced anything like this in our community," said photographer and healthcare preparedness coordinator Kayla Keigley. "Roads are destroyed. Neighborhoods are underwater. I am in shock and I work in the field of preparedness - this is something I work to deal with daily. Our community is in disbelief." A stranded seal sat on a Duluth, Minnesota, roadway after it was washed out of the Lake Superior Zoo during the June flooding. This image, shot by Ellie Burcar - who discovered the seal - went viral. Authorities soon arrived and the seal survived the ordeal. June's High Park fire, caused by extreme drought conditions, could be seen from the Horsetooth Reservoir in Larimer County, Colorado. "Climbing to this vantage point afforded me the opportunity to capture the fire crew on film at eye level as they flew by, and to look down into the heliport," said Bryan Maltais. "I could also also photograph the unique atmospheric conditions that the fire created." An avalanche tumbled down the surrounding mountains of the Annapurna Base Camp in Nepal in June. After hiking for more than a week in the Himalayas, J. Grant Trammell decided to shoot some photos from the safety of base camp. "It was a magically clear and still morning. I awoke just at 4 a.m. I made my way to a vantage point just above the Annapurna Base Camp and shot images for almost five hours." Wildfires burning in the foothills of the Colorado Springs mountains blanketed a nearby neighborhood with pitch-black smoke in June. "We ran outside and saw the side of the foothills getting engulfed by flames coming down on either sides of the quarry," said photographer Michael Kennedy. "Our subdivision quickly deteriorated into a war zone with police cars coming into the neighborhood with loud speakers announcing 'leave the area, under mandatory evacuation.'" A massive haboob, or dust storm, overtook Phoenix, Arizona in July, and Andrew Pielage knew he had to get it on camera. Racing up a mountain that was nearby, he skipped the official trail to get a better view and was able to capture it from a very unique angle. "I had made it just in time. You really get a good and scary sense of the size and magnitude of these types of storms. It will be a photograph I will never forget." Searing temperatures and high humidity brought a heat wave to Toronto, Canada, in July. "These past days have been brutal with the heat, the humidity. Tempers are short, electricity system is straining but not buckling... yet," photographer David Bradley told us at the time. Skies darkened over New York City as a storm moved into the area in July. "The storm was pretty mild, but seeing it come through was amazing," said photographer Jenna Bascom at the time. "Gorgeous clouds, great light." A historic drought in Terre Haute, Indiana, dried up a lake at the Wabashiki Fish and Wildlife Area, killing the fish living in it back in July. At the time, photographer Michael Gerringer said, "This lake attracts an impressive variety of birds and other wildlife, but when I walked out into the lake bed the only bird species I saw were a pair of turkey vultures overhead and a few red-headed Woodpeckers." Hurricane Isaac brought flooding to the streets of Fort Pierce, Florida in August. Trish Powers described the water as "waist deep" at times. See more Isaac images here. Many homes like this one collapsed in New Orleans, Louisiana after Hurricane Isaac hit in August. Eileen Romero was completely shocked when she came upon the scene only a block away from her home in New Orleans' Mid-City neighborhood. Dramatic flooding hit low-lying parts of Manila, Philippines, in August after continuous rainfall. Grant Orbeta captured stunning images like this one. Fuego Volcano spewed ash into the air in Antigua, Guatemala, shortly after it erupted in September. Photographer Jennifer Rowe said, "People who have lived here for more than 20 years have told me this is the biggest eruption they've ever seen." Rare cloud formations, called mammatus, were spotted in La Crosse, Wisconsin in September. The name "mammatus" comes from the Latin word manna, or breast. "After the storms rumbled through, I saw a yellow orange glow out the window," said Jim Jorstad. "I then grabbed my camera, began driving several miles up the hill, stopping to take photos along the way." Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic faced large-scale flooding as it was hit with Hurricane Sandy prior to the U.S. in October. Misael Rincon shot images of the superstorm and other hurricanes in 2012. A fleet of taxi cabs sat submerged in a flooded parking lot in Hoboken, New Jersey, after Superstorm Sandy hit the area in October. Photographer Jonathan Otto said, "The picture was taken from the 14th street viaduct looking over the corner of Jefferson and 14th street, where it appears New York stores new cabs." A house in Union Beach, New Jersey, was left standing despite being ripped apart from the winds of Superstorm Sandy in October. While photographing the area, Clifford Rumpf said each photo taken of the ravaged neighborhood was more shocking than the next. See more Sandy images here. Phnom Penh, Cambodia was hit with a torrential downpour of rain in October, causing flash flooding. Jim Heston was in awe of the fact that his camera was able to capture falling rain as well as it did. A nor'easter blew through Manhattan in November just after the area was hit by Superstorm Sandy, but a number of New Yorkers continued with business as usual. "I immediately rushed outside with my camera to capture some images, and, as the snowfall got heavier, I ended up walking from Upper East Side, down Fifth Avenue, to Times Square, taking snapshots of the snow bearing down on people and blanketing the streets," said Edgar Alan Zeta Yap. A December winter storm brought much needed moisture to drought-stricken Wisconsin. Jim Jorstad said, "The photos were stunning to capture. I drove up in the rural area of Chaseburg, Wisconsin. Some of the photos...were taken in and around some Amish communities nearby." Geneva, Switzerland Carbondale, Illinois San Francisco, California Duluth, Minnesota Duluth, Minnesota Fort Collins, Colorado Annapurna Base Camp, Nepal Colorado Springs, Colorado Phoenix, Arizona Toronto, Canada New York, New York Terre Haute, Indiana Fort Pierce, Florida New Orleans, Louisiana Manila, Philippines Antigua, Guatemala La Crosse, Wisconsin Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic Hoboken, New Jersey Union Beach, New Jersey Phnom Penh, Cambodia New York, New York Chaseburg, Wisconsin HIDE CAPTION << <

Low temperatures in Switzerland helped freeze Lake Geneva in early February. Rita Rautenbach got this amazing shot at the time. "'During the night and the day before, we had extreme temperatures where it got so cold that the spray made waves on the lake. As it sprays up it turns into ice immediately. It became layer on layer on layer. It became thick blocks of ice on the bench, on the cars." Hospital rooms were completely destroyed after a tornado hit Harrisburg, Illinois in February. Jane Harper, a nurse there, took this photo after moving patients out of harm's way. She went to check one of the patient rooms, and found that the room was no longer there. A lightning storm lit up the Bay Bridge in San Francisco, California in April. Phil McGrew shot 20-second exposures for 90 minutes in order to get shots like this. Severe flooding in Duluth, Minnesota, in June destroyed roads and left neighborhoods underwater. "We have not experienced anything like this in our community," said photographer and healthcare preparedness coordinator Kayla Keigley. "Roads are destroyed. Neighborhoods are underwater. I am in shock and I work in the field of preparedness - this is something I work to deal with daily. Our community is in disbelief." A stranded seal sat on a Duluth, Minnesota, roadway after it was washed out of the Lake Superior Zoo during the June flooding. This image, shot by Ellie Burcar - who discovered the seal - went viral. Authorities soon arrived and the seal survived the ordeal. June's High Park fire, caused by extreme drought conditions, could be seen from the Horsetooth Reservoir in Larimer County, Colorado. "Climbing to this vantage point afforded me the opportunity to capture the fire crew on film at eye level as they flew by, and to look down into the heliport," said Bryan Maltais. "I could also also photograph the unique atmospheric conditions that the fire created." An avalanche tumbled down the surrounding mountains of the Annapurna Base Camp in Nepal in June. After hiking for more than a week in the Himalayas, J. Grant Trammell decided to shoot some photos from the safety of base camp. "It was a magically clear and still morning. I awoke just at 4 a.m. I made my way to a vantage point just above the Annapurna Base Camp and shot images for almost five hours." Wildfires burning in the foothills of the Colorado Springs mountains blanketed a nearby neighborhood with pitch-black smoke in June. "We ran outside and saw the side of the foothills getting engulfed by flames coming down on either sides of the quarry," said photographer Michael Kennedy. "Our subdivision quickly deteriorated into a war zone with police cars coming into the neighborhood with loud speakers announcing 'leave the area, under mandatory evacuation.'" A massive haboob, or dust storm, overtook Phoenix, Arizona in July, and Andrew Pielage knew he had to get it on camera. Racing up a mountain that was nearby, he skipped the official trail to get a better view and was able to capture it from a very unique angle. "I had made it just in time. You really get a good and scary sense of the size and magnitude of these types of storms. It will be a photograph I will never forget." Searing temperatures and high humidity brought a heat wave to Toronto, Canada, in July. "These past days have been brutal with the heat, the humidity. Tempers are short, electricity system is straining but not buckling... yet," photographer David Bradley told us at the time. Skies darkened over New York City as a storm moved into the area in July. "The storm was pretty mild, but seeing it come through was amazing," said photographer Jenna Bascom at the time. "Gorgeous clouds, great light." A historic drought in Terre Haute, Indiana, dried up a lake at the Wabashiki Fish and Wildlife Area, killing the fish living in it back in July. At the time, photographer Michael Gerringer said, "This lake attracts an impressive variety of birds and other wildlife, but when I walked out into the lake bed the only bird species I saw were a pair of turkey vultures overhead and a few red-headed Woodpeckers." Hurricane Isaac brought flooding to the streets of Fort Pierce, Florida in August. Trish Powers described the water as "waist deep" at times. See more Isaac images here. Many homes like this one collapsed in New Orleans, Louisiana after Hurricane Isaac hit in August. Eileen Romero was completely shocked when she came upon the scene only a block away from her home in New Orleans' Mid-City neighborhood. Dramatic flooding hit low-lying parts of Manila, Philippines, in August after continuous rainfall. Grant Orbeta captured stunning images like this one. Fuego Volcano spewed ash into the air in Antigua, Guatemala, shortly after it erupted in September. Photographer Jennifer Rowe said, "People who have lived here for more than 20 years have told me this is the biggest eruption they've ever seen." Rare cloud formations, called mammatus, were spotted in La Crosse, Wisconsin in September. The name "mammatus" comes from the Latin word manna, or breast. "After the storms rumbled through, I saw a yellow orange glow out the window," said Jim Jorstad. "I then grabbed my camera, began driving several miles up the hill, stopping to take photos along the way." Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic faced large-scale flooding as it was hit with Hurricane Sandy prior to the U.S. in October. Misael Rincon shot images of the superstorm and other hurricanes in 2012. A fleet of taxi cabs sat submerged in a flooded parking lot in Hoboken, New Jersey, after Superstorm Sandy hit the area in October. Photographer Jonathan Otto said, "The picture was taken from the 14th street viaduct looking over the corner of Jefferson and 14th street, where it appears New York stores new cabs." A house in Union Beach, New Jersey, was left standing despite being ripped apart from the winds of Superstorm Sandy in October. While photographing the area, Clifford Rumpf said each photo taken of the ravaged neighborhood was more shocking than the next. See more Sandy images here. Phnom Penh, Cambodia was hit with a torrential downpour of rain in October, causing flash flooding. Jim Heston was in awe of the fact that his camera was able to capture falling rain as well as it did. A nor'easter blew through Manhattan in November just after the area was hit by Superstorm Sandy, but a number of New Yorkers continued with business as usual. "I immediately rushed outside with my camera to capture some images, and, as the snowfall got heavier, I ended up walking from Upper East Side, down Fifth Avenue, to Times Square, taking snapshots of the snow bearing down on people and blanketing the streets," said Edgar Alan Zeta Yap. A December winter storm brought much needed moisture to drought-stricken Wisconsin. Jim Jorstad said, "The photos were stunning to capture. I drove up in the rural area of Chaseburg, Wisconsin. Some of the photos...were taken in and around some Amish communities nearby." Geneva, Switzerland Carbondale, Illinois San Francisco, California Duluth, Minnesota Duluth, Minnesota Fort Collins, Colorado Annapurna Base Camp, Nepal Colorado Springs, Colorado Phoenix, Arizona Toronto, Canada New York, New York Terre Haute, Indiana Fort Pierce, Florida New Orleans, Louisiana Manila, Philippines Antigua, Guatemala La Crosse, Wisconsin Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic Hoboken, New Jersey Union Beach, New Jersey Phnom Penh, Cambodia New York, New York Chaseburg, Wisconsin HIDE CAPTION << <  1

1  2

2  3

3  4

4  5

5  6

6  7

7  8

8  9

9  10

10  11

11  12

12  13

13  14

14  15

15  16

16  17

17  18

18  19

19  20

20  21

21  22

22  23 > >>

23 > >>  23 best weather photos of 2012

23 best weather photos of 2012 "We knew days in advance, much more in advance, 48 hours in advance more than we knew in Katrina (in 2005)."

It could have been a much different story.

A month before the 1,000-mile-wide storm struck the Northeast, at the height of the hurricane season, the geostationary satellite that monitors the Caribbean and Atlantic -- where Sandy gathered strength -- stopped working. While there are dozens of American weather satellites in orbit, these geostationary spacecraft are crucial to predicting dangerous weather patterns.

America's aging satellites

Luckily, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, had a backup satellite to scramble into place. Without it, the early warning for Sandy's impending strike on the northeast might not have been as accurate.

That close call has meteorologists worried that, in this era of shrinking budgets, aging satellites might not get the expensive repairs they need to operate, and NOAA might not be able to purchase backup satellites.

Wind, rain, snow and fire: The storm that broke records, and hearts

Satellites like these are expensive -- $1 billion each -- and they take five years to build and launch.

Compare that to the cost of major storms, like Sandy which is estimated to have inflicted nearly $80 billion in damage in New York and New Jersey alone. Not to mention the cost in human lives.

"If there's a major failure of the satellites, that would be a major disaster and indeed we would be blinded in many respects," explained Kevin Trenberth, who heads climate analysis at the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

"We would not be able to see what's going on in the Earth's system as well as we can now."

Scientists can only wonder how many lives this technology could have saved on September 8, 1900, when a Category 4 hurricane slammed into Galveston, Texas, with no warning, killing at least 8,000 people. It would be another 70 years before satellites were used in weather forecasting.

Opinion: More voices needed in climate debate

A major failure of these satellites could pose a serious threat as climatologists and meteorologists warn that storms like Sandy could become more frequent and more powerful in the near future.

Lessons from Katrina

Seven years ago, the only thing protecting the low-lying city of New Orleans from a massive storm surge was an inadequate and outdated system of levees and floodwalls.

Lessons from Katrina and Sandy

Lessons from Katrina and Sandy  Katrina memories haunt New Orleans

Katrina memories haunt New Orleans  Looking back at Hurricane Katrina

Looking back at Hurricane Katrina After Hurricane Katrina slammed into the U.S. Gulf Coast in 2005 -- killing 1,800 people and inflicting $100 billion in damage -- Congress said never again.

Federal lawmakers spent $14.5 billion, mostly federal funds, to build a fortress around New Orleans.

Today the city is protected by 350 miles of stronger levees and higher flood walls that form a circle around New Orleans to keep any deadly storm surges at bay.

Among its most powerful new weapons: the largest storm-surge barrier in the world.

The massive barrier wall extends nearly 200 feet into the earth, and towers 26 feet above the water. It's reinforced by 350,000 tons of steel -- 50 times the amount in the Eiffel Tower.

The fortress has turned New Orleans into a giant bathtub. To prevent that bathtub from filling up during a major storm, the city built the world's largest water pumping system.

"(One station) can pump about 30,000 cubic feet of water per second, which is just extraordinary," said Garrett Graves, who is overseeing the state's new hurricane protection plan.

Katrina survivors offer advice to Sandy victims

At that rate, Graves explained, each of the 77 pumping stations could "fill an Olympic size swimming pool in about 4½ seconds."

It's arguably the best hurricane protection system in the country -- but Malcolm Bowman hopes it won't be for long.

That's because Bowman wants to build a barrier system across the 5-mile-wide opening to New York Harbor that he says could have protected America's most populated city from Sandy's devastating storm surge.

"If barriers and sand dunes had been properly built in the last eight years, none of this would have happened," he said.

Bowman leads the Storm Surge Research Group at Long Island's Stony Brook University. The group promotes a plan to create an elaborate system of barriers and causeways that would virtually flood-proof much of metro New York.

They say their "Outer Harbor Gateway" plan would cost billions of dollars less than the damage that Sandy inflicted upon the state of New York.

Bowman has spent years warning officials of the storm surge risk to New York City.

Less than a month after Katrina, he wrote an op-ed in the New York Times warning that the same thing could happen to New York City -- and outlining his storm barrier system solution to prevent it from happening.

He tried again in 2008 as part of a climate change panel convened by New York City's Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

But no barriers were built.

Experts warn of superstorm era to come

Today, Bowman is hopeful that New York authorities will green-light his plan. Gov. Andrew Cuomo is awaiting recommendations from a commission that he tasked with finding long-term solutions to protect his state from future weather calamities.

Two commissions on disaster preparedness and response have already offered their recommendations to the governor, who is expected to announce several proposals during his "state of the state" address on Wednesday.

Bowman's idea is not new: Similar barriers already exist in Stamford, Connecticut, and Providence, Rhode Island, and massive barriers are already in operation in the Netherlands and Russia.

With the rising sea levels -- a result of the shrinking polar ice cap -- experts including Bowman say the risk of massive flooding events is increasing each year -- and not just in low-lying communities like New Orleans.

"We have to start planning," Bowman said. "It's no longer every person for themselves. There's too much at risk. We have to do it."

The polar problem

Over the past 20 years, the global sea level has risen more than two inches as a result of Greenland's shrinking ice masses, according to Dr. Kevin Tremberth with the National Center for Atmospheric Research. That's because warmer temperatures are melting the polar ice caps.

Scientists map Antarctic sea ice

Scientists map Antarctic sea ice  Photographer captures glacial retreat

Photographer captures glacial retreat  Icebergs change Greenland's habitat

Icebergs change Greenland's habitat Recent satellite images from NASA showed unprecedented surface ice melt, with about 97% of Greenland's ice sheet showing signs of thawing.

These changes in the polar region are closely monitored by climate scientists, like Daniel Steinhage, whose team surveyed Greenland's shrinking ice with Polar 6 one of the most advanced research aircraft in the world. It will take months to evaluate the data gathered by the aircraft, including ice samples thousands of years old taken from deep within the ice sheet.

Uncovering Greenland's secrets

The Arctic is something like an archive of the Earth's climate and within its layers, researchers can find information on temperatures, the amount of precipitation, dust particles and ash from volcanic eruptions dating back 100,000 years.

"If we can explain the past, what happened there, then we can use the same programs to run them forward to see what the future will bring us," said Steinhage of Germany's Alfred Wegener Institute.

Long before the official lab analysis, scientist Sepp Kippstuhl can identify some unique patterns even with his naked eye.

What he and the other scientists are seeing is that Greenland's ice sheet is vanishing quickly -- a fact confirmed by the 2012 NOAA Arctic Report Card.

What's not entirely clear is how quickly, how often, and why temperatures changed in the past, something that these scientists are studying to better understand how our climate is evolving today.

For now, one thing is clear: Melting ice and rising sea levels increase the potential of a damaging storm surge.

"We expect several more feet in the next century," said climate scientist Adam Sobel. "So if you start with higher water ... the storm surge will be added on top of that. And so, we'll get a higher flood."

NASA scientist links climate change, extreme weather

Who's going to pay?

Superstorm Sandy brought a record-breaking 15-foot storm surge to New York Harbor (the storm surge is the level of water generated by a storm that's above the normal high tide). As Sandy approached New York, one buoy in the harbor measured a 32.5-foot wave -- nearly seven feet taller than the highest wave churned up by Hurricane Irene in 2011.

The enormous amount of water combined with the storm's powerful winds washed out the low-lying beachside neighborhood of Breezy Point, New York. The flooding is believed to have sparked a fire that burned down more than 100 homes.

Bowman said all of that devastation could have been avoided.

He said 30-foot-high sand dunes would have been enough to keep Breezy Point dry.

Opinion: Extreme weather and a changing climate

Projects such as that are expensive to build -- but sometimes the cost isn't the only hurdle standing in the way.

Some oceanfront residents in New Jersey have stymied a federally funded effort to build storm-protecting dunes -- even after witnessing the devastation from Sandy and Irene.

It comes down to a property rights issue: Homeowners must cede part of their land to the government through easements, where the dunes will be built. Some homeowners want the government to compensate them for land; others just don't want to allow the government to control the property.

"If we did sign it, we give up our land," Long Beach Island, New Jersey, resident Dorothy Jedziniak told National Public Radio. "Assignment means that your local politicians could assign a walkway, toilets, whatever."

Bowman believes the cost is too high for residents living near the coast not to act.

"People who lived here are paying for it in terms of human misery," he said. "But if you talk about paying for it in terms of rebuilding and the dollars, where are the dollars going to come from? And are the people of the Midwest going want to pay for protecting these privileged few people who are lucky enough to live on the ocean's edge? I don't think so."

Opinion: Why we should expect more weather disasters

Hospital rooms were completely destroyed after a tornado hit Harrisburg, Illinois in February. Jane Harper, a nurse there, took this photo after moving patients out of harm's way. She went to check one of the patient rooms, and found that the room was no longer there.

Hospital rooms were completely destroyed after a tornado hit Harrisburg, Illinois in February. Jane Harper, a nurse there, took this photo after moving patients out of harm's way. She went to check one of the patient rooms, and found that the room was no longer there.  A lightning storm lit up the Bay Bridge in San Francisco, California in April. Phil McGrew shot 20-second exposures for 90 minutes in order to get shots like this.

A lightning storm lit up the Bay Bridge in San Francisco, California in April. Phil McGrew shot 20-second exposures for 90 minutes in order to get shots like this.  Severe flooding in Duluth, Minnesota, in June destroyed roads and left neighborhoods underwater. "We have not experienced anything like this in our community," said photographer and healthcare preparedness coordinator Kayla Keigley. "Roads are destroyed. Neighborhoods are underwater. I am in shock and I work in the field of preparedness - this is something I work to deal with daily. Our community is in disbelief."

Severe flooding in Duluth, Minnesota, in June destroyed roads and left neighborhoods underwater. "We have not experienced anything like this in our community," said photographer and healthcare preparedness coordinator Kayla Keigley. "Roads are destroyed. Neighborhoods are underwater. I am in shock and I work in the field of preparedness - this is something I work to deal with daily. Our community is in disbelief."  A stranded seal sat on a Duluth, Minnesota, roadway after it was washed out of the Lake Superior Zoo during the June flooding. This image, shot by Ellie Burcar - who discovered the seal - went viral. Authorities soon arrived and the seal survived the ordeal.

A stranded seal sat on a Duluth, Minnesota, roadway after it was washed out of the Lake Superior Zoo during the June flooding. This image, shot by Ellie Burcar - who discovered the seal - went viral. Authorities soon arrived and the seal survived the ordeal.  June's High Park fire, caused by extreme drought conditions, could be seen from the Horsetooth Reservoir in Larimer County, Colorado. "Climbing to this vantage point afforded me the opportunity to capture the fire crew on film at eye level as they flew by, and to look down into the heliport," said Bryan Maltais. "I could also also photograph the unique atmospheric conditions that the fire created."

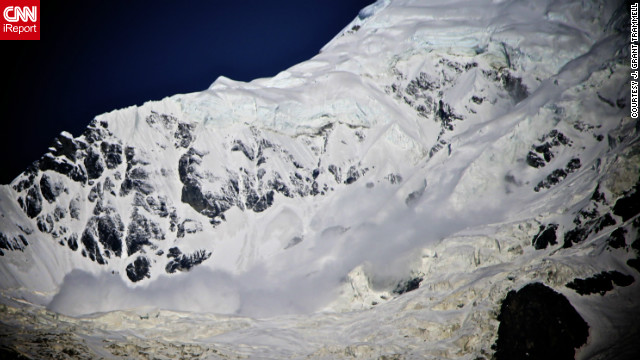

June's High Park fire, caused by extreme drought conditions, could be seen from the Horsetooth Reservoir in Larimer County, Colorado. "Climbing to this vantage point afforded me the opportunity to capture the fire crew on film at eye level as they flew by, and to look down into the heliport," said Bryan Maltais. "I could also also photograph the unique atmospheric conditions that the fire created."  An avalanche tumbled down the surrounding mountains of the Annapurna Base Camp in Nepal in June. After hiking for more than a week in the Himalayas, J. Grant Trammell decided to shoot some photos from the safety of base camp. "It was a magically clear and still morning. I awoke just at 4 a.m. I made my way to a vantage point just above the Annapurna Base Camp and shot images for almost five hours."

An avalanche tumbled down the surrounding mountains of the Annapurna Base Camp in Nepal in June. After hiking for more than a week in the Himalayas, J. Grant Trammell decided to shoot some photos from the safety of base camp. "It was a magically clear and still morning. I awoke just at 4 a.m. I made my way to a vantage point just above the Annapurna Base Camp and shot images for almost five hours."  Wildfires burning in the foothills of the Colorado Springs mountains blanketed a nearby neighborhood with pitch-black smoke in June. "We ran outside and saw the side of the foothills getting engulfed by flames coming down on either sides of the quarry," said photographer Michael Kennedy. "Our subdivision quickly deteriorated into a war zone with police cars coming into the neighborhood with loud speakers announcing 'leave the area, under mandatory evacuation.'"

Wildfires burning in the foothills of the Colorado Springs mountains blanketed a nearby neighborhood with pitch-black smoke in June. "We ran outside and saw the side of the foothills getting engulfed by flames coming down on either sides of the quarry," said photographer Michael Kennedy. "Our subdivision quickly deteriorated into a war zone with police cars coming into the neighborhood with loud speakers announcing 'leave the area, under mandatory evacuation.'"  A massive haboob, or dust storm, overtook Phoenix, Arizona in July, and Andrew Pielage knew he had to get it on camera. Racing up a mountain that was nearby, he skipped the official trail to get a better view and was able to capture it from a very unique angle. "I had made it just in time. You really get a good and scary sense of the size and magnitude of these types of storms. It will be a photograph I will never forget."

A massive haboob, or dust storm, overtook Phoenix, Arizona in July, and Andrew Pielage knew he had to get it on camera. Racing up a mountain that was nearby, he skipped the official trail to get a better view and was able to capture it from a very unique angle. "I had made it just in time. You really get a good and scary sense of the size and magnitude of these types of storms. It will be a photograph I will never forget."  Searing temperatures and high humidity brought a heat wave to Toronto, Canada, in July. "These past days have been brutal with the heat, the humidity. Tempers are short, electricity system is straining but not buckling... yet," photographer David Bradley told us at the time.

Searing temperatures and high humidity brought a heat wave to Toronto, Canada, in July. "These past days have been brutal with the heat, the humidity. Tempers are short, electricity system is straining but not buckling... yet," photographer David Bradley told us at the time.  Skies darkened over New York City as a storm moved into the area in July. "The storm was pretty mild, but seeing it come through was amazing," said photographer Jenna Bascom at the time. "Gorgeous clouds, great light."

Skies darkened over New York City as a storm moved into the area in July. "The storm was pretty mild, but seeing it come through was amazing," said photographer Jenna Bascom at the time. "Gorgeous clouds, great light."  A historic drought in Terre Haute, Indiana, dried up a lake at the Wabashiki Fish and Wildlife Area, killing the fish living in it back in July. At the time, photographer Michael Gerringer said, "This lake attracts an impressive variety of birds and other wildlife, but when I walked out into the lake bed the only bird species I saw were a pair of turkey vultures overhead and a few red-headed Woodpeckers."

A historic drought in Terre Haute, Indiana, dried up a lake at the Wabashiki Fish and Wildlife Area, killing the fish living in it back in July. At the time, photographer Michael Gerringer said, "This lake attracts an impressive variety of birds and other wildlife, but when I walked out into the lake bed the only bird species I saw were a pair of turkey vultures overhead and a few red-headed Woodpeckers."  Hurricane Isaac brought flooding to the streets of Fort Pierce, Florida in August. Trish Powers described the water as "waist deep" at times. See more Isaac images here.

Hurricane Isaac brought flooding to the streets of Fort Pierce, Florida in August. Trish Powers described the water as "waist deep" at times. See more Isaac images here.  Many homes like this one collapsed in New Orleans, Louisiana after Hurricane Isaac hit in August. Eileen Romero was completely shocked when she came upon the scene only a block away from her home in New Orleans' Mid-City neighborhood.

Many homes like this one collapsed in New Orleans, Louisiana after Hurricane Isaac hit in August. Eileen Romero was completely shocked when she came upon the scene only a block away from her home in New Orleans' Mid-City neighborhood.  Dramatic flooding hit low-lying parts of Manila, Philippines, in August after continuous rainfall. Grant Orbeta captured stunning images like this one.

Dramatic flooding hit low-lying parts of Manila, Philippines, in August after continuous rainfall. Grant Orbeta captured stunning images like this one.  Fuego Volcano spewed ash into the air in Antigua, Guatemala, shortly after it erupted in September. Photographer Jennifer Rowe said, "People who have lived here for more than 20 years have told me this is the biggest eruption they've ever seen."

Fuego Volcano spewed ash into the air in Antigua, Guatemala, shortly after it erupted in September. Photographer Jennifer Rowe said, "People who have lived here for more than 20 years have told me this is the biggest eruption they've ever seen."  Rare cloud formations, called mammatus, were spotted in La Crosse, Wisconsin in September. The name "mammatus" comes from the Latin word manna, or breast. "After the storms rumbled through, I saw a yellow orange glow out the window," said Jim Jorstad. "I then grabbed my camera, began driving several miles up the hill, stopping to take photos along the way."

Rare cloud formations, called mammatus, were spotted in La Crosse, Wisconsin in September. The name "mammatus" comes from the Latin word manna, or breast. "After the storms rumbled through, I saw a yellow orange glow out the window," said Jim Jorstad. "I then grabbed my camera, began driving several miles up the hill, stopping to take photos along the way."  Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic faced large-scale flooding as it was hit with Hurricane Sandy prior to the U.S. in October. Misael Rincon shot images of the superstorm and other hurricanes in 2012.

Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic faced large-scale flooding as it was hit with Hurricane Sandy prior to the U.S. in October. Misael Rincon shot images of the superstorm and other hurricanes in 2012.  A fleet of taxi cabs sat submerged in a flooded parking lot in Hoboken, New Jersey, after Superstorm Sandy hit the area in October. Photographer Jonathan Otto said, "The picture was taken from the 14th street viaduct looking over the corner of Jefferson and 14th street, where it appears New York stores new cabs."

A fleet of taxi cabs sat submerged in a flooded parking lot in Hoboken, New Jersey, after Superstorm Sandy hit the area in October. Photographer Jonathan Otto said, "The picture was taken from the 14th street viaduct looking over the corner of Jefferson and 14th street, where it appears New York stores new cabs."  A house in Union Beach, New Jersey, was left standing despite being ripped apart from the winds of Superstorm Sandy in October. While photographing the area, Clifford Rumpf said each photo taken of the ravaged neighborhood was more shocking than the next. See more Sandy images here.

A house in Union Beach, New Jersey, was left standing despite being ripped apart from the winds of Superstorm Sandy in October. While photographing the area, Clifford Rumpf said each photo taken of the ravaged neighborhood was more shocking than the next. See more Sandy images here.  Phnom Penh, Cambodia was hit with a torrential downpour of rain in October, causing flash flooding. Jim Heston was in awe of the fact that his camera was able to capture falling rain as well as it did.

Phnom Penh, Cambodia was hit with a torrential downpour of rain in October, causing flash flooding. Jim Heston was in awe of the fact that his camera was able to capture falling rain as well as it did.  A nor'easter blew through Manhattan in November just after the area was hit by Superstorm Sandy, but a number of New Yorkers continued with business as usual. "I immediately rushed outside with my camera to capture some images, and, as the snowfall got heavier, I ended up walking from Upper East Side, down Fifth Avenue, to Times Square, taking snapshots of the snow bearing down on people and blanketing the streets," said Edgar Alan Zeta Yap.

A nor'easter blew through Manhattan in November just after the area was hit by Superstorm Sandy, but a number of New Yorkers continued with business as usual. "I immediately rushed outside with my camera to capture some images, and, as the snowfall got heavier, I ended up walking from Upper East Side, down Fifth Avenue, to Times Square, taking snapshots of the snow bearing down on people and blanketing the streets," said Edgar Alan Zeta Yap.  A December winter storm brought much needed moisture to drought-stricken Wisconsin. Jim Jorstad said, "The photos were stunning to capture. I drove up in the rural area of Chaseburg, Wisconsin. Some of the photos...were taken in and around some Amish communities nearby." Geneva, Switzerland Carbondale, Illinois San Francisco, California Duluth, Minnesota Duluth, Minnesota Fort Collins, Colorado Annapurna Base Camp, Nepal Colorado Springs, Colorado Phoenix, Arizona Toronto, Canada New York, New York Terre Haute, Indiana Fort Pierce, Florida New Orleans, Louisiana Manila, Philippines Antigua, Guatemala La Crosse, Wisconsin Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic Hoboken, New Jersey Union Beach, New Jersey Phnom Penh, Cambodia New York, New York Chaseburg, Wisconsin HIDE CAPTION << <

A December winter storm brought much needed moisture to drought-stricken Wisconsin. Jim Jorstad said, "The photos were stunning to capture. I drove up in the rural area of Chaseburg, Wisconsin. Some of the photos...were taken in and around some Amish communities nearby." Geneva, Switzerland Carbondale, Illinois San Francisco, California Duluth, Minnesota Duluth, Minnesota Fort Collins, Colorado Annapurna Base Camp, Nepal Colorado Springs, Colorado Phoenix, Arizona Toronto, Canada New York, New York Terre Haute, Indiana Fort Pierce, Florida New Orleans, Louisiana Manila, Philippines Antigua, Guatemala La Crosse, Wisconsin Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic Hoboken, New Jersey Union Beach, New Jersey Phnom Penh, Cambodia New York, New York Chaseburg, Wisconsin HIDE CAPTION << <

{ 0 comments... read them below or add one }

Post a Comment